Rise and Fall

By Sidney Hinds

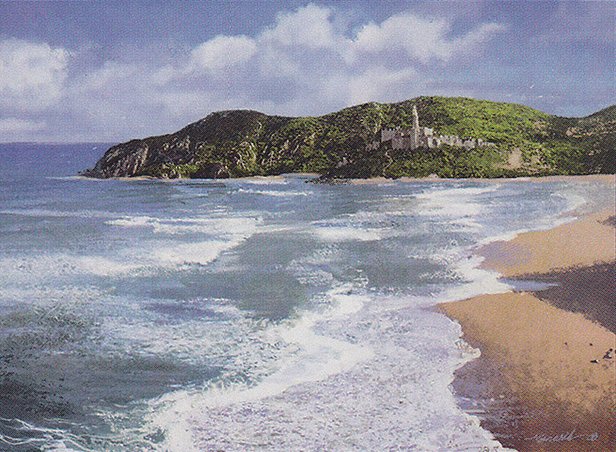

Vaash Vroga walked the beach on a nameless world, following in the wake of its creator.

It was not the first artificial plane she’d tread. Her journeys had taken her through the meditation realm of Nicol Bolas more than once (an oddly high number of times, truth be told, for a place closed off to so many). She had even spent a few painful, fleeting moments staggering through the ruins of old Phyrexia, failing to locate some ancient artifact or another at the behest of her now-discarded mantle, before the vile fumes of the place had overcome her.

This plane had a more convincing veneer of naturality to it, but the sand was just a bit too clean and golden, and the air not quite as fishy as it ought to be, this close to the sea.

“How much further?”

“Hm?” The creator turned his head back, slackening his pace by half a step. He was dressed in a simple sleeveless tunic of gold-trimmed white, with a cloak of the same colors that left his legs bare from the thigh down. Both garments glowed with an almost imperceptible light.

“How far is our destination?” Vaash gestured ahead.

“Ah.” The creator resumed his pace. “No destination. I thought a walk would be a nice change of pace for you.” He veered a degree to the right, and started up a low rise overlooking the shore. Tall, dark-green grasses grew in patches that quickly thickened as the beach rolled inland into a meadowed field. “’Tis nicer by far to walk in the open air, under the sun, than remain cooped up in some Tolarian dormitory.”

Vaash squinted up at the sky. It was decidedly overcast by now. There were rays of light still peeking through the seams in the clouds, but those were closing rapidly.

“Did you make that?” She asked. “It feels just like natural sunlight.”

“It’s a rescue,” the creator replied, his grin full of teeth. “A treefolk ‘walker pulled that sun into the Eternities about five hundred years ago to deny it as a power source to a rival. I plucked it from there.”

“The Battlemage Ravidel is as resourceful as he is formidable,” Vaash remarked.

“’Ravidel’, if you please. We will have a frank, straightforward conversation, unmuddied by titles or deference. After all, we are peers of the Multiverse, you and I.”

“No deference here.” Vaash held up her hands and gave a mock bow. “If the mighty Ravidel wishes to call me ‘peer’, I won’t deny him.”

Ravidel snorted. “Very good. You can lose ‘the mighty,’ but good.”

“Surprisingly humble for a centuries-old tyrant.”

“Hm.” Ravidel nodded, not turning back. “I find myself discovering and re-learning humility every century or so.”

The two Planeswalkers hiked a ways longer in silence. The fields were mostly empty, save for fireflies blinking among the blades. The grassy portion of the beach started to slope upward, and soon they were walking along a low ridge, a meadow to their right, and a straight drop of several yards down to the sands on their left. A clutch of children, human and goblin, were on the beach. A few tended to a fire, while others stood in the shallows, fishing. Several caught sight of Ravidel and called out. Ravidel acknowledged them with a wave and a nod.

“Well.” Ravidel paused at a small boulder set at a high rise in the hill, and perched upon it. “What do you think? Not bad for my first plane.”

Vaash regarded sea and sky, keeping her face set.

Ravidel chuckled. “Hard to impress a Planeswalker. Even one of you youngbloods.”

Vaash shrugged. “I’ve seen a lot.”

Ravidel didn’t offer a response to that. His breaths were short, and loud enough to be heard over the breeze. Awkwardly so. Oldwalkers were all like that in some regard. Still uneasy in the trappings of newly mortal bodies, even decades after the Mending had lessened the nature of the spark.

Maybe they just breathe loud because they miss being the center of attention.

“What is it you want out of life?”

Ravidel held a hand in front of his face. Five rings gleamed, one per finger, each inset with a stone. “What does Vaash want for Vaash?” As Ravidel spoke, points of colored light peeled off from the rings and swirled in his open palm.

“’Vaash’ has not had much time alone for Vaash. But I am content in the freedom I enjoy as a mage and ‘walker to do as I please.”

“Or as others please that you do?”

Vaash regarded Ravidel. He held her gaze, lights spinning faster and faster in his palm.

“This talk is going to be about Leshrac, isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“Why?” Vaash rested a hand on her hip. “Why bring me here to lecture me on my tormentor?”

“I am uniquely qualified to do so: I know what it is to be twisted to the ends of another Planeswalker. I know what it is to twist others to my ends. And, of course, I knew the Planeswalker who has most recently twisted you to his ends.”

The colored lights slowed and hovered, and condensed into a figure: a wrinkled, white-haired man, with flame around his brow, and a rippling tunic the color of night.

“Leshrac. A peer of my first master, Faralyn. Along with Tevesh Szat, they conspired to slay one of their fellow ‘walkers and use the life force to escape their joint imprisonment on Dominaria. Instead, their plotting led to my own death and sparking, and the death of my dearest friend.”

“He’s supposed to be dead,” Vaash whispered, eyeing the figure. “Supposed to have died decades ago in the Mending, shoved face-first into a rift.” She shrugged her shoulders again, to reassure herself they were still bare.

Un-mantled.

“Yes,” Ravidel said. “And as I understand, you have your own schemes for him.”

Vaash scowled “I have not spoken of schemes to do with Leshrac. To you or Jodah or Ral.”

“But you have spoken about him to Jodah, and he has sense enough to read your intentions between the lines. Vengeance. Plain and simple.”

“Yes, plain and simple.” Vaash walked past Ravidel, moving slightly past him up the slope. “Intentions so plain and simple, in fact, that we don’t need to discuss them further.”

“Jodah wishes you to reconsider. I wish for you to reconsider.”

Vaash shook her head. “I have a responsibility to my homeland. Urborg has many enemies, and Leshrac is too potent a foe to leave unattended.”

“Urborg is important to you.”

“Urborg is…at the core of what drives me. Freedom for Urborg, and those of Urborg. All the world dismisses us as a sulfurous swamp, yet all the world cannot help but interfere with our sovereignty. I would see an Urborg free of tyrants.”

“Noble and high-minded.” Ravidel nodded. “Were you brought up among freedom fighters, or do you come by these ideals yourself?”

“Hah!” Vaash spat upon the grass. “My ideals are my own. ‘Freedom’ couldn’t have been further from the aims of those who raised me.”

Ravidel nodded. “Your parents?”

“I lost my parents to the Breathstealers when I was six.” Vaash hissed. “Urborg’s infamous death cult. They took me to feed into the meat grinder of their mercenary service.” Vaash paused. Her chest was filling and falling rapidly. She closed her eyes and slowed her lungs, letting the rise and fall become deeper, slower, and then regular again.

“And yet they taught you many lessons,” Ravidel observed, as she opened her eyes again. “Your prowess in death magic demonstrates as much.”

Vaash shrugged. “A lesson can come from anywhere. It does not make the teacher good, even if the lesson is. Always there was an ulterior motive with my elders among the Breathstealers. They taught power for no purpose but to farm us out as glorified magical assassins. Breathing exercises, lessons in eating mana, artifacts of power… all given to make us powerful pawns. I was taught that the greatest thing I could aspire to in life was to die, and merge with the great nightstalker” Vaash turned toward the water. “My inclinations to freedom are antithetical to the Breathstealers.”

“That’s where the mantle came from.” There was the faintest hint of a question in Ravidel’s voice.

“Jodah told you of the mantle?”

“A power-storing and consuming garment that bears the mark of Leshrac? Of course he did. I am, as I said, one of the few living authorities on the Walker of the Night.”

“I thought you didn’t care for titles.”

“It sounds like this particular title might be salient, given the mantle’s origins.” Ravidel looked her up and down. “Was he a Breathstealer himself?”

“A few of my teachers among the Breathstealers thought he might be some legend from the cult’s past, perhaps even the Spirit of Night itself. As for me… I was nothing special to them, and the mantle was just a means. A pretty basting on another sacrifice intended to raise another iteration of their night-stalking god.” Vaash’s mouth twisted. “Well, I guess they succeeded in the end, didn’t they?”

Ravidel nodded. “Perhaps the mantle was a contingency. In case another ‘walker ever succeeded in doing to Leshrac what… well, what happened to him, in the end.”

The image of Leshrac in his palm shuddered, dissolving into points of light that leapt up into the air, and spiraled in a wide ring overhead. The lights twisted around one another, fusing into a broad, tangled, rainbow-hued circle.

“Let me tell you a tale.” The ring blazed with light and the image of a woman emerged, with a warrior’s build and cascading blonde hair. Beside her stood an old man with a walking stick, and a cap upon his head.

“Tev Loneglade was a Planeswalker,” Ravidel began. His voice had a slight echo to it. More vanity. “Old and powerful. Not the friendliest of ‘walkers, but content to keep to himself.

“He had a sister, Tymolin. One precious to him, on whom he expended his magical prowess to protect and keep alive. She was taken from him-”

A flurry of figures swirled around the two—figures in white and black. They surrounded the tall woman, and she fell out of the disk, limp.

“-and slain. So Tev swore vengeance, and became Tevesh. Tevesh Szat.”

The hunched and burly man turned reptilian and blue-scaled. Tentacles blossomed around the ring, and he reached down toward them.

“Szat swore vengeance against his sister’s killers, and then against Dominaria, and eventually, once free of the Shard of Twelve Worlds, against everything and everyone. He sowed ruin across all Dominaria and every other plane he could reach.”

Steaming tears streamed from the burly thing’s red-hot eyes as it tore through figures—black and white at first, then green, blue, and red.

“Tevesh Szat slew my dear friend at the Summit of the Null Moon, to escape the Shard. Tore them away from me just as the Icatians took his sister from him. He did not do this to spite me, but he did it nonetheless, and in doing so spurred me to become a beast not entirely unlike him. I became a scourge to many, mortal and walker alike, all in the name of revenge-”

The image shifted. A red-haired man was struck dead by Ravidel’s magics. A man in a turban assaulted a minotaur with magics, and was in turn cut down by a golden-haired figure wearing dark glasses. Szat screamed in a dome of glass and metal as electricity cooked his flesh.

“-and all for naught. I accomplished precious little against the ‘walkers who actually manipulated me, other than to hurt the ones who once wished to help me. Tevesh Szat evaded me for centuries, only to die at the hands of some greasy-fingered tinkerer.

“Taysir and I sealed Leshrac away on Phyrexia for a time, but by then… vengeance and hatred had become so core to my being that I was indistinguishable from the walkers I had sworn vengeance upon.”

Ravidel closed his eyes. “So it was that the cycles of vengeance claimed me.”

Vaash snorted. “And let me guess, it all starts with one bad decision.”

Ravidel nodded. “It starts with a compromise. A bending of principals, justified by belief in the good of your ends. Then another compromise, no worse than the first, but justified further because two compromises cannot possibly be that worse than one. Then, eventually, comes a complete break from your principals, and before long, a snowdrift of compromises have buried the ruins of whoever you once were.”

“So what’s the solution?” Vaash spread her hands. “Never compromise? Never take risks?”

“Not at all. Simply do not fool yourself when a compromise comes. When you break with your ideals, acknowledge the break, and reassess yourself. Otherwise you’ll have no idea what you’ve become, and in trying to reconcile the self with the lost ideal, you will lose yourself further. The person you are now, or the person who compromises. You can’t be two people at once.”

“What if I want it both ways?” Vaash drew her hand in a line through the space between Ravidel and herself. “Who says I must choose between the Vaash I am and the Vaash who takes vengeance? Why must it be an inherently corrupting process?”

“Everything we do changes us, Vaash Vroga.” Ravidel clenched his fist. “One does not pursue a creature like Leshrac, or even the shadow of Leshrac, without risk to oneself and others. Inherently self-altering risk. Did you not compromise yourself significantly in your pursuits for artifacts to feed to Leshrac’s mantle?”

Vaash scowled. “It seemed a better path than nourishing it with the breath of orphans.”

“And yet look at what you did do. Destabilizing Zendikar. Attacking your fellow ‘walkers.”

“Walkers who did not care to understand-”

“And Shiv?” Ravidel’s eyes flashed. “Were your actions there the work of the ambitious, high-minded mage who wishes to free the planes of tyranny?”

“That… was a compromise. A bad one.”

“A man like Deniz-”

“I know!” Vaash interrupted, hotly. “I know and I regret it! I told myself he was Benalish, they fight against the Cabal too. I saw them as allies, and I thought one intervening on Shiv would be beneficial…”

She tapered off as Ravidel raised an eyebrow.

“It was a compromise,” She said, turning back to the sea. A trail of smoke was blowing off the children’s fire, swept inland and up the slope below them, where the warm breeze from inland carried it back over the sands and the waves. “There was power to be gained in having an ally who controls the mana rig.

Enough perhaps to power the mantle without having to go hunting artifacts on other planes.”

“That must have been quite the burden, sating Leshrac’s hunger.” Ravidel lowered the ringed hand.

“Sustaining the mantle.”

“It was painful,” Vaash whispered, “but I thought it a necessary task, to fight against beasts like the ones who gave the mantle to me.”

“It is the cycle.” Ravidel said. “The Breathstealers wronged you. The Cabal wrongs your homeland. And in your efforts to right those wrongs, you have spread the cycle of wrongs wider still. The only solution can be this: Remove yourself from the cycle, and feed it no longer.”

Vaash was silent, regarding Ravidel. His breath was slower now, and steady, though his stomach was rising and falling with each breath.

“Do you like the person you are, Ravidel?”

Ravidel blinked. “I…what?”

“Would you say that you like yourself? As you are now?”

“I am proud of what I am now,” Ravidel said. “Considering my past. He gestured toward the children, who were cooking their catch over the fire. “Where once I ruined lives, now I provide preservation of both. A whole plane, safe and peaceful, for the orphans I left in my wake, and for their descendants.”

“Would you be who you are now, if you hadn’t done all those things before? If you hadn’t fallen into the cycle of vengeance? If you had not learned all you know now from the mistakes you made?”

Ravidel pursed his lips. “No, I suppose I wouldn’t be. Still, I would excise those years of my life from existence if I could. All those lives lost, people killed… were they worth it for one mage to become a better man?”

Vaash stared at him, and shrugged.

“Yes,” Ravidel said, smiling sadly. “Fair enough.” He smiled at Vaash, though it was strained. “I suppose we live with all versions of ourselves at all times, don’t we?”

Vaash shrugged again.

Ravidel closed his hand. The ring of mana above them collapsed into his fist and was extinguished. Raindrops, minute pinpricks of coolness in the still-warm air, dotted Vaash’s face and arms.

“I’d welcome you to stay here a while,” Ravidel said. “To think over vengeance before you take it. The planes will carry along fine in your absence. Here you can be at peace with the Multiverse. Apart from the cycle.”

“It is not better to leave the cycle behind than to remain,” Vaash snapped. “Power not used for good out in the Multiverse is power that might as well have been snuffed out. All the good Planeswalkers of old who died… would the outcome for the Multiverse at large not be the same if they had just disappeared to a pocket plane, never to be seen again?”

Vaash took a breath. “Your question before, if your growth was worth the cost of your sins, it’s the wrong way of looking at things. Nature does not care about moral equity. Maybe you are a better person for your reformation and experiences, but it’s all of little benefit to the planes if you stay here, closed off from it.”

“Be careful how much you presume the Multiverse needs people like us.” Ravidel crossed his arms. “The denizens of the Multiverse endured before we were born, and will do so long after you and I die.”

“Yes,” Vaash replied, “But I would rather they endure without tyrants than with. With fewer storms and calamities.”

“An answer for everything.” Ravidel let his hand fall.

“Yes. This is a conversation, isn’t it?”

Ravidel opened his mouth as if to respond, but seemed to think better of it. He exhaled instead, still loud and abrupt, and sat back down upon the stone.

“It is that. I forget myself.” He shrugged, and gestured towards Vaash. “Please.”

“The cycle of wrongs and responses is as natural to human intercourse as the predator-prey system. Even the gods must live within them the best they can.” Vaash clenched her fist. “As walkers, don’t we have a privileged position? A rare perspective? How is it good to remove ourselves from the cycles when our privilege makes us among the few who can ease the suffering of those within?”

Ravidel stared at her, though by the way he worked his jaw, he did appear to be considering her words.

“I think, perhaps, we are both wrong.”

Vaash raised an eyebrow. “Oh? So an old dog can still ponder new concepts?”

“To stay in the cycle and let it buffet us about is beneath a walker. Even if we see the cycles for what they are.” Ravidel opened his hand. His rings glowed faintly. “But to abandon it is, as you suggest, a waste of our potential. We can be proactive in our good as much as in our wickedness.” Ravidel stood, and clapped his hands together. “We cannot leave the cycle, and it makes no difference to simply remain.” He began to pace the grass.

Vaash moved to follow his pacing. “So we guide the cycle.”

“We influence it the best we can.” Ravidel pounded a fist into his hand. “Use our knowledge having been tossed about by the Multiverse to determine how to best spin to the ends of peace. Perhaps find an equilibrium where those within the cycles do not just survive, but thrive.”

Vaash nodded. “Remove the worst elements to keep the cycle from spinning out of control. Elements like Leshrac.”

Ravidel stopped in place. The winds were picking up again. “Snuffing Leshrac will be dangerous. There will be risk and a great danger of collateral damage if not handled carefully. It would be completely understandable if you preferred to leave this task to me.”

“Fuck off, old man. I am the one allowing you to accompany me in this endeavor.”

Ravidel laughed at that. Really laughed, a cackle that cut through the growing bluster of the storm. A madman’s laugh, no mistaking it, but Vaash found it oddly comforting.

“I would ask one thing of you, at the outset of our partnership here.”

Vaash raised an eyebrow. “What would that be?”

Ravidel clasped his hands together behind him. “If we do this, once its over… while it’s underway… I want you to think long and hard about who Vaash Vroga is, and what she wants for herself, should she ever allow herself to rest.” He held out a hand. “Agreeable?”

“Tolerable,” Vaash clapped hands with him, and they shook. “I look forward to getting to know both of us.” The air was still warm, but now thicker droplets of cool water were beginning to pepper them, wetting her face and bare forearms.

“Arcades’ Scales, that’s a nice feeling,” Ravidel remarked as their hands unclasped. He had his face upturned to the sky, nostrils flaring.

“You’re breathing wrong.”

“Hm?” Ravidel turned to look at Vaash sidelong.

Vaash drew in a long breath, letting her chest swell slowly. She gestured at her breast. “Expand as you inhale-”

She let it out, whistling into the wind. “Draw in as you let your breath go. Let your chest rise and your lungs fill. Your lungs, not your belly.”

Ravidel copied her for several repetitions. “Hm. The benefit being?”

“Oxygen gets into the blood; you’ll live longer, old man.” She smirked at him. “And waste less time with spells of vigor.” She nodded her chin at his emerald ring, which still glinted brighter than the others.”

Ravidel snorted. “Impudent. You’ll make a fine protege.” He breathed in and out again, with a thoughtful grimace. “And is this a technique of…?”

“Just good practice in many cultures, on many planes.” Vaash turned back to the sea, and nodded. “But yes, learned in Urborg.”

“A lesson learned can be put to good use no matter the source,” Ravidel said. “I heard that once, but in my old age, I can’t quite remember where from.”

Vaash snorted. The rain water had soaked her hair by now, and warm trickles of water were pouring down her neck and face. It did feel tremendous.

She allowed herself a smile.

A laugh.