Gods and Monsters

This content was deleted from the Magic website during an update. The original page can be accessed via Wayback Machine here.

By Doug Beyer

What if everything you knew was an insidious lie?

What if your deepest, most ardently held beliefs were founded on a historical mistake?

What if, despite your lifelong convictions, an incontrovertible truth arose that could destroy the foundations of your value system?

Today we’re talking about the spiritual beliefs of some of the races of Zendikar, the hope-rending reality that lurks beneath them, and some of the behind-the-scenes creative work that went into creating both.

Three’s Company

As the creative team was putting together the style guide for Zendikar, a sort of world-building miracle happened. My teammate Jenna Helland and I each independently wrote about a trio of gods worshipped by Zendikar humanoid races—she wrote about the deities of the merfolk, and I wrote about the deities of the kor. That wasn’t so crazy in itself; it felt right for both of those races to have a spiritual belief system, and three happens to be a comfy, comfy, comfy number for groups of things. But it felt like a discovery—clearly Zendikar had three of something, and something preternaturally important.

“That’s interesting,” we said. “Maybe what the merfolk call Emeria, Ula, and Cosi are the same supernatural entities that the kor call Kamsa, Mangeni, and Talib.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s go into the merfolk beliefs first.

The Merfolk Deities

The merfolk of Zendikar divide up the world into three realms, each of which they believe is ruled by a divine being. You may even be familiar with the names of their deities already: Ula, god of the sea’s depths; Emeria, goddess of the sky and wind (once called simply “Em” in parts of the Zendikar style guide); and Cosi, the trickster god, ruler of the land and earth.

The merfolk recognize these divinities as the forces that drive the world, usually adopting the creed of one of the three as their own. Emeria, also the name used to refer to the ruined floating castle in Tazeem believed to be where the goddess once dwelt, brings an ethereal wisdom to her devotees. While merfolk are not native to Emeria’s sky realm, they connect with her airy mysticism, many of them following her creed and striving to learn ways to restore her to rule in her floating castle once again.

Followers of Ula, the water-realm deity, pride themselves on being blunt and straightforward in their dealings with others. Ula-creed merfolk operate the famed research facility at the Lighthouse at Sea Gate and make excellent navigators and ruin scholars.

Almost no one admits to being an adherent of Cosi, the trickster. Blamed for the misfortunes of the world, Cosi is seen as a force of chaos—and yet the merfolk believe in his dynamic, incredible power. If someone could channel the untapped forces ruled by Cosi, they say, that individual would be one to fear, indeed.

The Kor Gods

The kor worship a small, simple pantheon of deities, each one based on an aspect of nature. Kamsa, the goddess of the wind, called “the breath of the world,” fills the kitesails of the kor and fills the skies with game such as windrider eels. Mangeni, god of the sea, “blood of the world,” fills the canyons and streams with pure, rushing water, but also punishes the stagnation of misguided builders who attempt to set down overly permanent roots in one place. Talib, the god of the earth, “body of the world,” crushes the unworthy in rockslides and gravity wells but also provides herbs and fungi to forage along the kor pilgrimage routes.

Gods in the Details

So my writer-pal Jenna and I had built these austere little pantheons for the Zendikar races we were developing, and after the style guide was completed, we noticed how closely their structure lined up.

I mean, look at this chart. The chart is truth. The chart does not lie.

| Merfolk deities | Kor gods |

|---|---|

| Emeria Merfolk deity of the realm of sky, wind, and clouds Ostensibly female | Kamsa Kor goddess of the wind, breath of the world Ostensibly female |

| Ula Merfolk deity of the water realm Ostensibly male | Mangeni Kor god of the sea, blood of the world Ostensibly male |

| Cosi Merfolk trickster-deity of all other realms Ostensibly male | Talib Kor god of the earth, body of the world Ostensibly male |

We didn’t make a huge effort to connect them at the time; we merely noted the fun coincidence and moved on. But the odd correspondence wouldn’t be tossed aside so easily. What seemed at first like a throwaway idea took root in our brains, twining its tendrils in our cerebral folds.

I find that a lot of world-building ideas make their way to this way. A cute idea, even one that comes up after the style guide, incorporates itself into our thinking and becomes a necessary part of that year’s setting. It spawns tangential ideas of its own, little creative scions that creep and spread, and the idea ends up holding up so much of the superstructure in our minds that it becomes part of the foundation. From the outside it’s probably hard to tell the difference between ideas that came from the style guide and those that came as a result of thinking after the style guide—I mean, I hope it’s hard to tell, we try to spackle over our nails—but some of the coolest ideas form as we’re writing art descriptions, seeing sketches, creating card names, and writing flavor text.

So we adopted that idea, at least in a casual way—that the three deities recognized by the merfolk were the same as the gods of the kor. There would be friction between the races on this point; you would not want to get in between a white-aligned, self-assured kor and a blue-aligned, accuracy-obsessed merfolk when they’re discussing religious metaphysics. Proud of their spiritual heritage, both races would probably snort and cross their arms if anyone would even suggest that their deities were just different aspects of the same entities, the same phenomena with different trappings.

But there was one more aspect to this spiritual convergence that had yet to arise.

The Eldrazi

We’ve been pretty hush-hush about the Eldrazi on the site so far. But the truth is getting out, tidbit by terrifying tidbit.

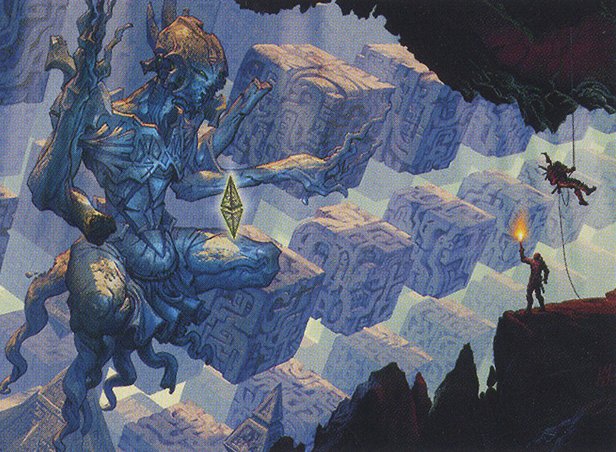

The Eldrazi are nightmarish, titanic, ætheric creatures native to the Blind Eternities. They exist only to feed, and they feed on the energy of worlds: mana energy, life energy, spell energy, natural energy. Thousands of years ago, three Eldrazi monstrosities descended on Zendikar, drawn by the plane’s fierce and primal mana. They spawned entire subraces of minor Eldrazi, called “brood lineages,” to help them pillage and consume, and proceeded to lay waste to the plane.

Three powerful planeswalkers—a dragon called Ugin, a stone-shaping lithomancer about whom little is known, and a vampire known as Sorin Markov—came to Zendikar’s aid, but even they could not destroy the Eldrazi. In a dramatic, desperate act of spellcraft, the planeswalkers trapped the Eldrazi on Zendikar, dooming the plane but hoping to spare the rest of the Multiverse from the Eldrazi hunger. Zendikar became the Eldrazi’s prison, held fast by a mystical lock-spell concealed deep within a subterranean chamber known as the Eye of Ugin. The three planeswalkers left the plane, hoping their trap would hold.

The plane was nearly stripped of its resources. But Zendikar survived. The brood lineages died off and the Eldrazi colossi fell inert, and Zendikar began a slow process of recovery.

Thousands of years passed, and the Eye of Ugin held.

Reborn in a crucible of disaster, the world of Zendikar became a wild, savage place. The world’s creatures and even its lands evolved ferocious defenses to ward off any being that would dare feed on it again.

As of Worldwake, the natural landscape of Zendikar seems to have sensed that a threat is upon it once more.

Horrifying Things Come in Threes

There are three legendary Eldrazi creatures in Rise of the Eldrazi, and a brood lineage of other Eldrazi creatures styled around each of the three legends. We had known that there would be three of them for a while; we had been preparing a supplementary style guide for the block’s dramatic third act, complete with an entirely new set of concept illustrations. The look of each brood lineage lines up with the legend that spawned it; I’m excited for you to see what our artists came up with when Rise of the Eldrazi releases.

Kozilek, Butcher of Truth is one of the legendary Eldrazi.

The second is called Ulamog, the Infinite Gyre.

The third, the largest and most powerful legendary Eldrazi of them all, has not yet been announced.

Notice anything about those two Eldrazi names? Kozilek. Ulamog. It almost seems like they’re derived from the names of two of the merfolk deities, Cosi and Ula. It’s almost as if the Eldrazi legends form one more column of the chart o’ deities—one more metaphysical parallel that creates the spiritual skeleton of Zendikar.

Wrong.

Yes, they match up. Yes, the Eldrazi legends belong on the same tripartite chart. But the chronology is backwards. In truth, the merfolk deities Cosi and Ula are derived from dim memories of Kozilek and Ulamog. If you’re at all a spiritual person on Zendikar, it’s horrifying realization time.

Religion is thousands of years old on Zendikar. But the Eldrazi came first.

Letter of the Week

Brandon has a question about the flavor of Ice Cage.

Dear Doug Beyer,

Considering you’re the master of flavor in the Magic R&D, perhaps you’ll be able to answer my question.

Ice Cage is a pretty decent limited card, but horrible in constructed. Obviously, it’s because of the fact that it gets destroyed when the creature it’s imprisoning is targeted. My question is simple. Why? Why does targeting a creature frozen in ice suddenly thaw it? I can understand why a Giant Growth would break the cage, because the creature is suddenly too large for its former confinement, but why would changing a creature’s color with something like Cerulean Wisps cause the cage to fail? Why would equipping a creature with a Sword of Light and Shadow break the ice? How would the creature even be able to grab the sword without being able to move?

Brandon

I love this question. Everybody’s got slightly different intuitions about flavor, Brandon, and so what feels satisfyingly flavorful to one player might seem off to another. You’re a man with exacting flavor standards, and I applaud that. “Being targeted” is indeed a very broad phenomenon in the world of Magic, and there are plenty of examples of targeting that don’t seem functional or powerful enough to break a magical cage of ice.

However, those odd examples indicate a strength of the game, not a weakness. A properly flavorful card is a sweet spot between flavor and game complexity. It’s not a failing that Ice Cage is broken by things other than Bonesplitters, Quietus Spikes, and targeted spells with Fire in their names—those lines of text would make the card and the game’s rules needlessly complex and unfun, and arguably still wouldn’t get across the flavor of a cage of ice any better than the targeting trigger (and I doubt such specific conditions would make people enjoy flavor). A stylish, simple line of text is easy to remember, fast to play, and more fun than a litany of drawbacky flavor clauses.

Sure, there will always be times when you can come up with nonsensical flavor situations, but that’s an indication of the beauty and freedom of the game. We write the text on the spells, but you get to decide how to cast them.