Killing Time

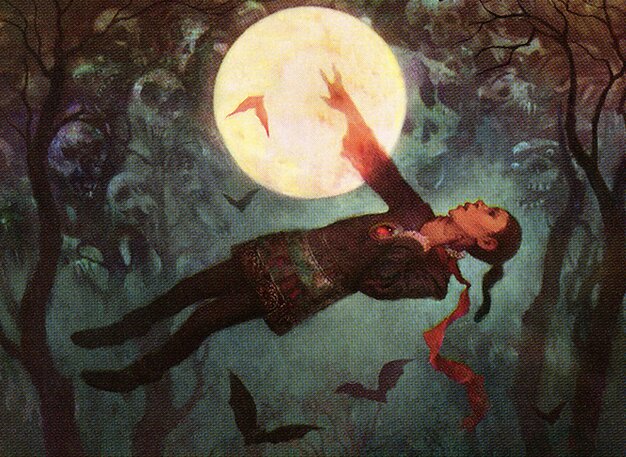

The trouble with immortality was finding things to do. So she had gone mad, and that helped pass the time.

These days she had family to occupy her, so she filled her hours with worry. She worried about her grandson, who she thought was looking skinny. She brought him good things to eat—monks, and priests, and even the occasional virgin—and he always thanked her fulsomely, but he hardly ever partook. She had trapped and stewed an abbot for him, once, which he had professed to enjoy. The key was to cook them low, and slow, braising in their own juices—you had to do it like that, when the meat was old and tough.

He had thanked her for her thoughtfulness when she pulled back the cloche, but he had mostly just moved the abbot around on his plate, while they made small talk about the weather.

He took his nourishment in other ways, she understood that. Still, a growing boy ought to eat.

She kept mementos of his achievements, like any proud grandmother would, although she was running out of cupboard room for the skulls. Still, that was a tractable problem. There were entire wings of the castle she had not explored yet, even after hundreds of years. There would be more than enough wall space to mount any future trophies.

The key to bleaching skulls, she had discovered, was the same as braising an abbot: you had to render them low and slow. Patience was key, but immortality bred patience, and centuries spent trapped in a coffin had left her with a fixity of purpose which she understood, though only vaguely, that others who were not so gifted did not share.

Skulls continued to fascinate her, even after all these years. Each was unique, and each told a story. You could read a lifetime’s worth of trauma in just the contour of a cheekbone.

Skulls were better than books, if you knew how to look.

She wondered what her own skull would look like, should the time ever come. She had left instructions for its preparation in a place where she knew they’d be found.

She kept spellbooks and scrapbooks, and lost sleep over missing pages. A thief had taken one, once, and she had sworn to get it back. She asked her grandson about that, from time to time, and he always told her the same thing: “Be patient. I have a plan.”

She wondered how he could not notice that patience was all she had.

In the years since the interlopers had gone, she had found new ways to amuse herself. She had muddled up their stories, until even the Death Speakers could not agree what was myth and what was canon. If she could not exact vengeance on their bodies, she would take revenge upon their memories, instead.

And history, unlike the body, was incapable of self-repair.

The one with the angels had left a journal—an apologia of sorts—full of self-pity and sermonizing. She had read it, then wished she had not—the words made painful sounds in her head.

At first, she had meant to burn the book, but in the end she had reused it: rising the ink out, then sketching skulls on the pages. Even for an immortal, there was no sense in wasting good paper.

In the evenings, she tinkered with her spells and hexes. It was remarkable what you could do with even the simplest techniques once you had power and the willingness to use it, and she had left her inhibitions in the casket. With just a slight variation on a standard hex she had once turned an Aysen bureaucrat inside-out. That had made a lovely sound, so she wrote the recipe down, but the resulting mess was a lot to clean up, and her knees were not what they once were.

There were rats behind the baseboards that ran up her bed posts at night. She would lie awake and watch them, enjoying the way their eyes glinted in the moonlight. She read poetry to them, and fed them plates of pickled toes. They seemed significant to her, for reasons she could not recall.

Her grandson really was looking skinny—she hardly ever saw him eat. It drove her to distraction.

He said they would go through the Gate, soon, although he did not quite know what it would mean. She was looking forward to it, a change would do him good. And there would surely be skulls on the other side.

Exciting new people, with exciting new skulls.

There was a chime kept sitting on her mantlepiece, un-rung, and gathering dust. She took it down sometimes just to see it, because it was a pretty thing. But there was a reason she had once decided not to ring it, though she could no longer remember just what that reason was.

It was a shame, really. She liked music, always had. It was one of the few things she remembered from the pre-madness days—a memory bleached and faded, and now just one more skull.

Maybe she would ring the chime someday, she reflected. Some day when the omen was right.

She would know, she decided, when the time came.

For now, she had her family, and her skulls. There would always be family, and there would always be more skulls.

The trouble with immortality was finding things to do, but she had ways to kill the time.