All That Came Before

This content was deleted from the Magic website during an update. The original page can be accessed via Wayback Machine here.

By Leah Potyondy

Cho-Akhan is a caretaker for the dead, living with her family in a small Cho-Arrim village in the depths of the Rushwood. Life in the village is quiet and peaceful, and the long arm of Mercadia City seems impossibly far away…

The morning began just the same as so many before: with a dead person.

Cho-Akhan was used to dead people. Her mother—well, the mother who had given birth to her, not the other one—was a caretaker for the dead, taking in and caring for deserted Cho-Arrim bodies so that their souls could be sent on to rest. Her father had been a caretaker, too, before he’d joined the ranks of his charges. ‘Akhan came, in fact, from a long line of such people. So when her day started with rising with the sun, washing and dressing, and joining her mother Cho-Fihad in preparing the body of a woman from their village, it wasn’t anything out of the ordinary.

The woman, a scout named Cho-Hanni, had been sick. Something had eaten up her insides while life still pumped through her, and the stink of her body when they had received her was, ‘Akhan supposed, unusual. ‘Fihad ran a hand across Cho-Hanni’s ashen face and told ‘Akhan to go out and fetch more sweet herbs to pack into the body before they sent her on her way. Cho-Hanni wouldn’t want to make her way down the river knowing that her body was left smelling like that, even though they were going to burn it in the end.

‘Akhan rolled her eyes when ‘Fihad wasn’t looking. ‘Fihad had a lot of ideas about what dead people did and didn’t want. Lots of adults in the village did. As though a dead person were in a position to want anything. ‘Akhan cared for the dead, but she didn’t think—as her mother clearly did—that the dead cared back.

“Will you at least think about the garden this time?” she asked as she grabbed her gathering bag. “It would be so much easier for us to grow the herbs here. There’s plenty of space in our plot, and I could bring back some extra to plant.”

‘Fihad shook her head, smiling an indulgent smile. “My persistent daughter. You know those herbs do best in the woods. Herbs growing in the garden would miss the wildness. They’d miss the trees and the river.”

‘Akhan forced a smile and hitched up her bag. At the age of sixteen, she knew better than to argue.

But she wanted to. Oh, she wanted to. ‘Akhan played it out in her head as she made her way down the dirt road that lead out of the village. It was ridiculous that she had to go so far to get something that they could just grow at home. She was good with plants. So was her brother, Cho-Ran. She knew he’d help her with the garden whenever he wasn’t off with the other scouts. It wasn’t even like ‘Fihad would have to do any work…

She came to the river and followed it a ways, listening to the noises it made as it wound its slow course past rocks and roots. ‘Fihad thought it was full of souls, going to wherever it was that Cho-Hanni was headed. Of course she did. ‘Akhan cut north, away from the river and toward the tangled pocket of woodland where the sweet herbs grew. She thought about planting the garden anyway. What would ‘Fihad do, pull the herbs up by their roots when she found them growing behind the house?

She stewed over it all the way up to her gathering place, lost completely in the tightening spiral of her own thoughts. She would have kept stewing, too, had a great horned troll not come crashing through the trees in front over her, right into her path.

She tripped backward in surprise, catching her foot on a thick root and tumble-skidding down a steep incline that, embarrassingly, she had overlooked. The incline had a sort of concave pocket at the base, though, and she pressed herself tightly into the hiding space it afforded, hoping desperately that the troll hadn’t noticed her.

The troll was big, and very angry. Clods of dirt scattered down the incline and off the little earthen shelf over ‘Akhan’s head. She buried her face in the dead leaves. Go away, she thought insistently. Go away, go away, go away.

After what felt like an eternity or two, the sound of the troll’s footsteps receded, tromp-tromping off through the trees and underbrush. Probably stomped all over my herbs, too. That would figure. ‘Akhan moved into a crouch, brushing the worst of the dirt off of her clothing. She had just readjusted her bag on her shoulder when something caught her eye.

She had gone to collect herbs many times before. This was the closest to the village that they grew, and she seldom trekked any farther into the dense forest. She had not, however, spent much time at the bottom of this particular drop-off, hiding from angry trolls, so she could forgive herself for never having seen the chiseled stone pillar that looked suspiciously like half a doorway. The pillar was barely taller than she was, covered over with thick, creeping vines. And beyond it…

She was pulling the vines away before she quite realized what she was doing. Her efforts revealed more crumbling stones, fitted together imperfectly and accented with carved scribbles that she presumed were some sort of writing. This was a doorway, all right. A doorway with a wall fitted right over it.

Unbearably curious, she pulled stone after stone away until the opening was wide enough to allow her to squeeze through. Inside was a dry mustiness, barely stirred by the currents of air passing through the newly unsealed door. ‘Akhan felt her way along the passage, fingers brushing against crumbling dirt. Soon, the dim light from the door disappeared altogether. She wished she had something to light her way, but it was too late to go back. She was committed.

The passage abruptly opened into a small room. She could feel the walls drop away, the space opening around her into even deeper shadow. And there, in the middle of the room, she could make out a shape, standing out just slightly against the dark. Like a plinth, and something on top of it…

A body.

‘Akhan crept closer. An old body, she realized. An unbelievably old body, wrapped up in a desiccated sheet. And what was that all over its face? It seemed to be giving off a barely perceptible light. ‘Akhan crept closer, reaching out gingerly with her hands…

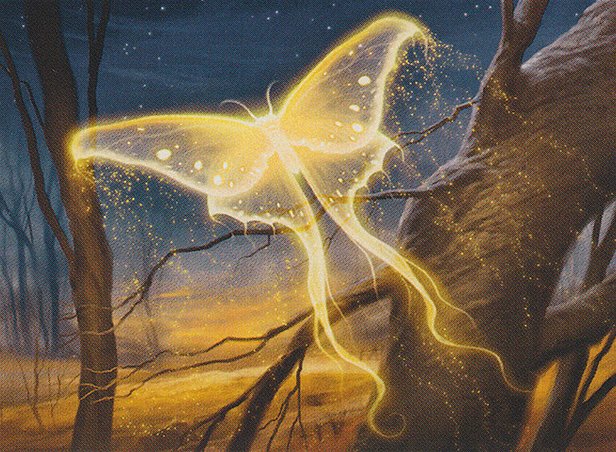

A glowing mass erupted around her probing fingers. She jumped backward, heart pounding against her rib cage. Moths, she realized. A flurry of softly glowing moths, rising out of the object beneath her hands.

Surrounded by the dry fluttering of dozens of feathery wings, she peered down at the face again, illuminated now from the outside.

A mask, she realized. The body was wearing a mask, shattered into pieces.

No…not shattered. The pieces of the mask were embedded in the mummified flesh of the face. She imagined what it would feel like to have skin growing over bits of ceramic, integrating, welcoming it in…

Suddenly, she couldn’t be out of the cave fast enough. The moths rose in a whirlwind around her.

‘Akhan returned home with a bag full of herbs, and while mother Cho-Shadi may have raised her eyebrows as she polished her long spear, mother ‘Fihad said nothing about the delay. Instead, she simply smiled and directed ‘Akhan to help prepare the herbs.

“I saw a troll today,” ‘Akhan said, keeping her voice casual as she packed the herbs into small linen pouches. ‘Fihad had already removed Cho-Hanni’s blackened organs, and ‘Akhan’s pouches would soon take their place.

Mother ‘Shadi, who wasn’t afraid of anything, shifted almost imperceptibly. Mother ‘Fihad sighed and took a pouch from ‘Akhan. “They’ve been restless. Much more…” Her brow furrowed. “Something bad is coming. Rushwood is afraid.” Flaring nostrils. “This smells of Mercadia City.”

‘Akhan set her jaw. It was an old argument, this business about Mercadia City. “Nothing bad is coming, Mom.” She handed off another pouch of fragrant herbs. “Mercadians don’t come here. They just sit in their big shiny city, and they never send soldiers.”

Mother ‘Shadi snorted. “Listen to our grown-up daughter, ‘Fihad. So knowledgeable in matters of empire. So sure that that big polished cage does not move.”

‘Akhan felt her jaw tighten. “City folk like their cities, and cities do not move. Mercadia won’t come, and neither will anything else. If anything, you should worry about making me walk so far to collect herbs when there’s perfectly good land out back. ‘Ran would help me work it, and I wouldn’t almost get eaten by trolls!”

‘Fihad smiled the shadow smile that meant she was thinking of ‘Akhan’s father, reminded by something in ‘Akhan’s face or voice or movement. Maybe that was why she’d chosen ‘Shadi after her husband was six years in the river. Rough ‘Shadi, quick with a spear, spare with her words, as different from ‘Akhan’s father as a jaguar was from a lamb. ‘Akhan, feeling the prickly discomfort that she felt every time she saw that smile, found herself blurting out:

“I found a dead person, too.”

‘Fihad looked up from Cho-Hanni, concerned. “Not someone from the village?” she asked. “Is the sickness spreading?”

‘Akhan shook her head quickly. “No, no. Not like that. Someone dead a long time, hidden in a cave. She had a mask—” and here she raised her hands to her face for emphasis “—built right into her face.”

‘Fihad’s eyes sharpened. “Sounds like you found one of our old shamans. Not many left—Rushwood tends to swallow them down.”

‘Akhan raised an eyebrow. “Shamans? Shamans just read the harvest and bless the hunt. Read nice words when people die. That sort of thing.” They don’t push ceramic pieces into their skin.

“Maybe not our shamans. But my mother used to tell me stories. She told me that a long time ago, our ancestors honored their people with masks. Not just their own ancestors, but the people who were alive, too. Their parents and siblings and children who shared their table.” She looked down at Cho-Hanni, waiting to be stitched and swathed. “The living along with the dead.”

“Uh-huh.” ‘Akhan passed fine bone needles to her mother, sharp enough to pass clear through a finger before you could even feel it. “Living and dead. Got it.” She didn’t want to seem interested. ‘Fihad always took that as an invitation to pull her down into ramblings about old mysticism and old rivers carrying old souls. But she was interested, and that was almost more annoying by itself than any of the stuff that ‘Fihad believed in.

‘Fihad took the proffered needles from her daughter and threaded one, bending to the task of putting Cho-Hanni’s body back together. “It sounds strange, doesn’t it? But those shamans, they made their masks of all different pieces. Like a puzzle, or a mosaic. Each piece was meant to represent or channel a different aspect of their people. Kind of like a picture of who they were and what they could do. There’s great power in that sort of togetherness. It’s a shame what we’ve forgotten.”

“A picture, sure.” ‘Akhan made a show of shaking her head, completing her work in silence. But deep down inside, she felt a little thrill.

Long hours had passed since Cho-Hanni’s body was brought to the river, resting on a bier of fragrant cedar and wrapped in the colors of mourning. Their shaman—their normal shaman with his normal face—had said his words over the body while mother ‘Fihad shielded her eyes. She said that caretakers were supposed to cover their eyes so that the soul could slip from the body and into the river without everybody watching, and ‘Akhan had made the gesture too without really meaning it. She’d been doing it since she was little. The river was peaceful and beautiful, a good place for a funeral. What it wasn’t was some magical soul road. Cho-Hanni was gone. End of story.

Now it was dark, and a heavy summer rain pounded against the roof. Over the rain, she could hear ‘Ran snoring heavily on the other side of the cloth wall that divided them. Her older brother had returned home from ranging just after Cho-Hanni’s body had been burned down to ashes and scattered into the river. Unsurprisingly to ‘Akhan, he carried no news of encroaching Mercadian soldiers or city-built war engines, though he did have an improbable story about a bear attack that made mother ‘Shadi snort and cuff him across the back of his head. Judging by his snores, he would sleep deep and wake early, ready to be up and moving. He’d even agreed to help her with her herb garden, offering a conspiratorial wink when mother ‘Fihad wasn’t looking. It would be a good day.

The night noises should have lulled her off to sleep, but instead they pried her senses open. She kept thinking about the dead shaman woman and her dead shaman picture mask, covered up and forgotten in that crumbling dirt room.

At least she’s got weird moths to remember her. Give her a light to see by…

Before she quite knew what she was doing, ‘Akhan was fully dressed and sneaking out the door, trusting the rain and ‘Ran’s abundant snores to cover the sound of her passage. The pounding rain shocked her skin and flattened her black hair against her head in an instant.

She set out toward the river.

She retraced her steps from the day before, following the curve of the rushing water. The river was running wide and wild, spilling its banks, exulting with the rain. She was just getting ready to peel away into the trees when something stopped her dead in her tracks.

That something was mother ‘Shadi, matted with rainwater, long spear in her hand. She stood stock-still, looking at some great mass that lay at her feet. The water that cascaded off the head of the spear was tinged red.

“Dead inside,” ‘Shadi murmured as ‘Akhan approached. She angled the head of the spear downward to point. Fascinated, ‘Akhan followed the line of the spear down to the corpse of the horned troll sprawled in the mud. ‘Shadi had slit its belly open, and stinking, blackened innards spilled from the gash.

“Like Cho-Hanni,” breathed ‘Akhan. The smell of the sickness pushed up through the pounding rain.

Her gut lurched.

More people in the village got sick. It didn’t take long. Cho-Annu, the spearmaker. Cho-Biaal, who took all day to wash her clothing so that she could hear all the gossip on the banks of the river. Cho-Tunni, who kept three dogs and no husbands. People ‘Akhan had known all of her short life, brought down one by one. The healers tried everything that they knew, old arts and new measures alike, but still the sick burned up with fever. One by one, they followed the path that Cho-Hanni had trod. Cho-Annu, Cho-Biaal, Cho-Tunni, all laid out in the home of ‘Akhan and her mothers, ashes for the great river.

‘Ran with his crow-feather hair, devoted oldest son, beloved brother of ‘Akhan, felt his lungs curl and blacken within him. He died in their home, and they barely had to move him three feet to prepare him for his journey.

His journey. The words soured against the back of ‘Akhan’s tongue, unspoken and bitter. There would be no garden, now. Mother ‘Fihad stroked her son’s hair, still damp with old sweat. “The river will guide him true,” she said. “It will take him to rest.”

A furry brown moth, trapped inside the house, battered against the ceiling, looking for a way out. ‘Akhan watched it struggle, feeling helpless and angry. “There’s nothing special about that river,” she snapped. “‘Ran is dead.” And then, quieter: “He’s not coming back.”

‘Fihad said nothing, and ‘Akhan pretended that she didn’t see that her mother was crying as she prepared the body of her son. She clenched her jaw, teeth grinding, and counted out the pouches of herbs. She had made so many, lately. For the first time, she envied her mother’s belief. ‘Fihad would find peace somewhere in this, even with her dead son in her arms. But for herself, ‘Akhan was certain that there would be no peace.

The moth continued to struggle, its small body slamming into the ceiling again and again. ‘Akhan wanted to scream. There’s a window, she thought. It’s right there. Just fly down, and you’re free.

Just fly down.

The mask leapt into her thoughts. The dead shaman’s mask, down down down under the ground, lit with old knowledge and a whisper of dusty wings. She would have seen this, ‘Akhan thought. If she really did have power, if Mom is right, she would have seen this coming. Wouldn’t she?

‘Akhan passed a hand over her eyes and found a veil of tears.

‘Ran was nine days in the river when ‘Shadi brought news. Cho-Arrim scouts, galvanized in the wake of ‘Ran’s death, had ringed their eyes with his ashes and disappeared into the Rushwood wilds, ‘Shadi among them. They had returned in the predawn with reports of Mercadians, small bands of soldiers bearing the crest of their shining city. The soldiers were traveling light. They carried few weapons. But in their wake, the trees shuddered and groaned. Roots twisted in the earth, and tamarins fell from their high homes to rot in beds of dead leaves.

They were bringing sickness to Rushwood.

“Nothing but scavengers,” ‘Shadi muttered as she cleansed the dirt from her wiry arms. “They’ll kill us all off without even laying a finger on a single Cho-Arrim, then pick over our bones for whatever’s left.”

Rushwood is afraid.

Mercadia does not come here.

‘Akhan had never felt so guilty in her life. The feeling sat in her bones, heavy and dark. She would have staked her life on ‘Fihad’s fears being the stuff of superstition, a grown-up who didn’t understand that the world had changed. Instead, ‘Fihad was right, and ‘Ran had paid for ‘Akhan’s error with his own life.

He was dead because of her. Because she hadn’t believed her mother. Because she only knew how to prepare a body, not save one. Because, because, because.

That night, when the moon was high above the canopy, ‘Akhan left her house and its parade of dead kinfolk. Brown moths fluttered in the air around her, wings catching in the moonlight. They watched her go.

She padded through the wet chill, drifted alongside the river, made her way down into that old tomb and its shaman mask. Her body felt hollow. Her heart felt filled with fluttering moths. Moths in the moonlight. Moths under the mask. She felt that if she were to open her mouth, they would come bubbling out of her throat.

She stared down at the shaman, long dead and inscrutable. She stared, and then she opened her mouth. The moths filling her body poured out. The moths filling the mask rose up and scattered.

She screamed, and screamed.

At first, it was wordless. A lifetime of confidence, shattered. An older brother who lived life out in the wild woods, dead on the floor of their home. A father who didn’t wake up, and a mother who cried every night while her young children tried not to listen. A thick film of ashes coating the back of the rushing river. Mercadia.

Mercadia.

Mercadia.

She slumped against the dirt wall, exhausted. “Why?” she whispered between dry lips. Why did this happen? Why are we dying? Why are you here with your mask and your secrets, watching my world fall apart?

She closed her eyes.

“The Cho-Arrim don’t remember,” said a voice in her head. “They knew, once. How to be many.”

“But…how?” she murmured. She knew that she was falling asleep, speaking to an empty room. It didn’t bother her. She had already been wrong about so much.

“The mask has power,” came the voice again. “You make it with pieces of your world. You become a reflection of your people.” A hesitation. “You lose yourself, though. You make yourself into a picture of everyone else, but it covers you.”

Tears squeezed out through ‘Akhan’s closed eyelids.

“Uh-huh. It covers you. Got it.” She pulled in a shuddering breath. She felt the crushing weight of mother ‘Fihad’s rightness, of mother ‘Shadi’s bloody spear, of the capital city that had waved its hand and killed ‘Ran a million miles away. All of those deaths, filling up the air with ashes.

“I don’t mind being covered,” she said. “If it saves my people, I don’t mind. I haven’t helped my family. I couldn’t save my brother. It isn’t so great a loss, to lose me.”

The voice sounded sad, when it spoke again. “It is always a great loss when a family loses a child.“

‘Akhan felt herself smiling. “Then I’ll make sure that no more families need to.”

The decision was made. Moths battered the air around her, a rising storm of wings and light. ‘Akhan knew that she wouldn’t have time to build a mask before the wave of the empire came crashing down on them…but maybe she wouldn’t need to.

Her eyes cracked open. She looked to the body.

Pain.

‘Akhan could feel the blood on her face, cascading from the places where her skin was opened. Under the light of what seemed to be hundreds of soft wings, she had pulled the mask pieces from the dead shaman’s face. The shaman hadn’t put up much of a fight. Not giving herself the chance to hesitate, ‘Akhan had started pushing the dusty ceramic shards into her own face.

For ‘Ran. For my mothers. For the Cho-Arrim.

The pain cracked her open like ripe fruit. Bloody red flowers bloomed in the cracks of her skin.

There was power, too. Surges of it, building behind her teeth and against the insides of her wrists, shuddering in great swaths across the lean muscles of her back. For brief moments, as she made her stumbling way back toward her village, she could swear that her feet left the ground behind. For a beat of her heart, she would float, only to snag her foot in the next step and narrowly avoid falling to her knees. A great strength flooded her limbs, then drained out and left her struggling to place one foot in front of the other. She blinked her eyes and Rushwood was replaced with rows upon rows of Mercadian military, sun glinting off their helmets. And facing them, mother ‘Shadi at the front of mustered Cho-Arrim warriors. Standing ready.

Another blink, and there was the forest again, the armies vanished.

Mercadia is coming, she thought through the haze of juddering power. Mercadia is coming, and mother ‘Shadi will try to drive them back.

She needed to reach them. She needed to get to the village and find ‘Shadi. Find their warriors. They would need the weapon that she brought, the weapon—

With a sickening lurch in her gut, she realized that she wouldn’t be in time. She had thought to bring a great weapon, something to throw back at the invaders, to show the strength of the Cho-Arrim, but her body and mind were breaking apart under the strain of the dead shaman’s mask. The power was borrowed, and could not find a way to take root inside ‘Akhan.

Her skin felt wet.

The river. She was in the river.

In the moment before she submerged, she thought she could see the surface of the water softly glowing. River full of souls, she thought. Mother ‘Fihad would want me to cover my eyes.

She passed beneath the glowing surface, feeling the cool water fill in the gaps between her flesh and the mask shards. Relief. Relief from the pain, relief from the flickering vestiges of long-buried power. She opened her eyes.

The dead stared back at her.

They were everywhere. Cho-Arrim people, like her, and people older than Cho-Arrim, eddying in the current. She supposed that she should feel afraid. Or, perhaps, transcendent.

Oh, there you are, she thought instead. She wished ‘Fihad could see. All of the ashes poured into the river, all of the rites…it wasn’t empty at all.

A lump formed in her throat. I thought you were gone. All of you, I thought you were gone.

I’m sorry.

One of the souls reached out and touched ‘Akhan’s broken skin. A coolness separate from the water suffused her. A piece of ceramic detached from her face and drifted toward the riverbed.

No, I need that…she thought. More souls brushed against her, knitting her flesh and pushing out the mask. Stop, you can’t…

The hope for the Cho-Arrim fell away from her in ceramic splinters. She wondered dimly if it was possible to cry underwater.

The final piece fell away.

The water around her began to hum.

The soul closest to her reached out and stroked her face. ‘Ran, she realized. This is ‘Ran. It was like remembering somebody from a long time ago, or looking at them from a great distance. His fingers brushed the tracery of fresh scars, and ‘Akhan felt her body flood with light. Where before she had felt uncontrollable bursts and ebbs of unpredictable power, she instead felt a steady pulse, connecting her with every soul in the river. They were tied, bound up in each other, travelers on the last long road.

A single, perfect picture.

Suddenly, ‘Akhan felt herself being wrenched upward. The souls around her scattered like a cloud of moths as she burst up through the surface of the river. Somebody was gripping her arm and shouting her name. A face, somehow familiar. Mother ‘Shadi, eyes wild with worry, pulling her up onto the riverbank.

“I know you…” said ‘Akhan. Her thoughts were sluggish. “You’re one of my mothers.”

‘Shadi barked a laugh. “Listen to this daughter of mine, forgetting my face just because she fell in the river.” She had tears in her eyes, and wiped them away with the heel of her hand. Her eyes widened, then, and she took in ‘Akhan’s face for the first time.

“‘Akhan, what happened? Who did this to you?”

‘Akhan lifted a hand and touched the skin. Raised patterns greeted her fingertips, circles and whorls of scar tissue. She sat up carefully, pulling away from ‘Shadi’s grasp, and peered into the river. It no longer seemed to glow, but the scars did. Reflected in the water, they looked just like a mask.

She smiled a slow smile and stood. A few moths, skimming the surface of the water, fluttered up and danced around her head.

“‘Shadi? Did you find her?”

‘Fihad appeared from around a bend in the river and came running toward them. When she saw ‘Akhan’s face, she stopped in her tracks, tears in her eyes. “Oh, ‘Akhan,” she said, brushing her daughter’s face with her fingertips. Her smile was that sad smile, the one that spoke of ‘Akhan’s father and that now spoke also of ‘Ran. “I had hoped that we wouldn’t lose you, too.”

‘Akhan lifted her arms and enveloped ‘Fihad in a warm embrace. “I am Cho-Akhan,” she whispered against ‘Fihad’s ear. “I am Cho-Ran. I am Cho-Hanni, Cho-Annu, and Cho-Biaal. I am Sia-am-Erh, interred under the grove. I am you, Cho-Fihad. And I am Cho-Shadi. I am our family. I am the family of our family.”

‘Fihad pulled away and stared at the face of her daughter. Her eyes were filled with fierce pride and bottomless sorrow.

‘Akhan nodded and lifted her head. Strength surged through her limbs. She felt the river in her blood, the forest spreading through the length of her body. A chorus of voices sang in her heart, Cho-Arrim and the people who gave birth to the Cho-Arrim. An army would fall to her, she knew. Mercadia would behold her, and know that she was many voices. A mosaic of all that her people were, and all that they could be.

“Show me our army,” she said to ‘Shadi, the woman who had been her mother.

The Mercadians were expecting to find a single, weakened village, full of sickness and ripe for the taking. They were not expecting to find every Cho-Arrim that had ever called Rushwood their home. They were not expecting a fight.

Won’t they be surprised?